Machine learning

Multiple types of automated learnings

- machine learning vs deep learning vs reinforcement learning vs online learning

Leo Breiman Statistical Modeling: the two cultures

Here is the abstract

_ There are two cultures in the use of statistical modeling to reach conclusions from data._

One assumes that the data are generated by a given stochastic data model. The other uses algorithmic models and treats the data mechanism as unknown.

The statistical community has been committed to the almost exclusive use of data models. This commit- ment has led to irrelevant theory, questionable conclusions, and has kept statisticians from working on a large range of interesting current prob- lems.

Algorithmic modeling, both in theory and practice, has developed rapidly in fields outside statistics. It can be used both on large complex data sets and as a more accurate and informative alternative to data modeling on smaller data sets.

If our goal as a field is to use data to solve problems, then we need to move away from exclusive dependence on data models and adopt a more diverse set of tools

Some dubious statistics

-

correlation is not causation => spurious correlation website

-

statistical significance - p-values

Machine learning

Linear Regression

Legendre (1805): First publication of the method of least squares, which is the basis for linear regression.

Gauss (1795–1809): Independently developed and formalized the method, contributing significantly to its statistical foundation. chat.mistral.ai

Linear regression

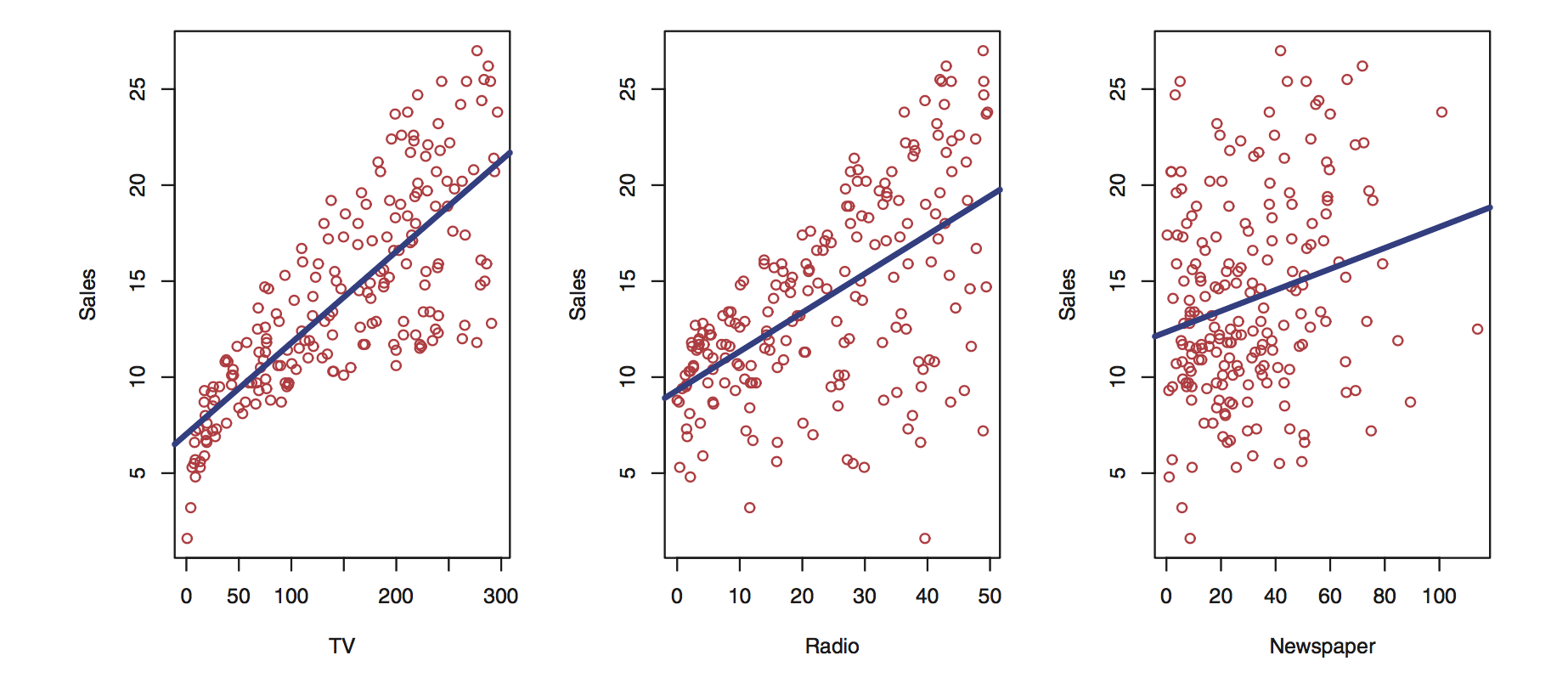

context: tabular data. - predictor variables - target variable : the thing you want to predict

Simple model : linear regression

sales = a * radio + b * TV + c * newspaper + noise

you try to find a, b, c so that you can predict sales

- find the line closest to the points.

- minimize the distance between the line and the points.

- distance = difference between the predicted value (the points on the line) and the actual value (the real data).

Linear Regression Rocks!

- simple

- explainable

- been around for litteraly ages

- you cna understand the dynamics within the data.

- very much in use today

- implemented everywhere: R, python statsmodel, excel, …

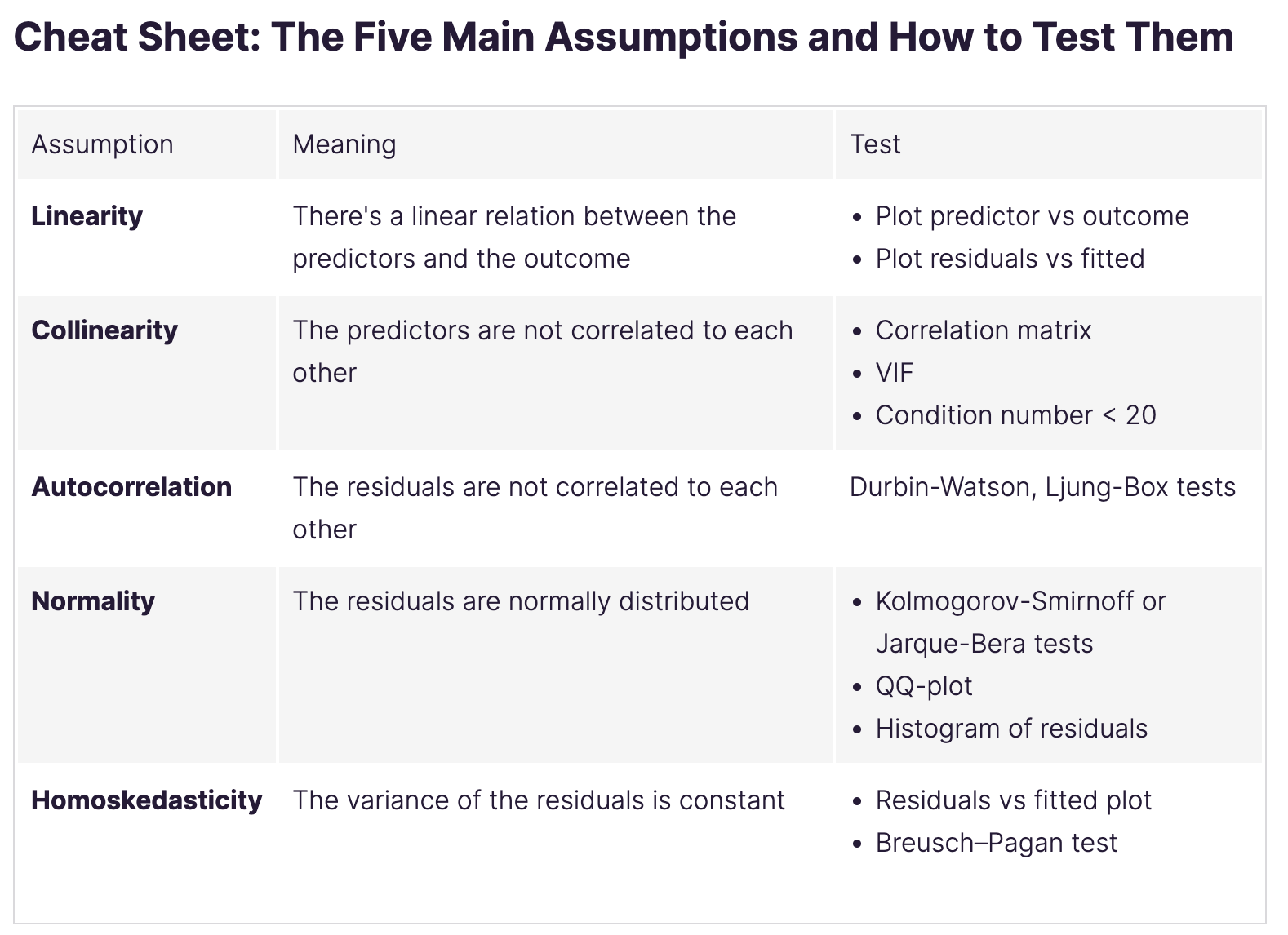

Some hypothesis needed

Method of least squares

The goal is to minimize the error between what the model predicts and the actual values

In the case with 2 predictors (x_0 and x_1) and 1 target (y), the model is:

y_pred = a* x_0 + b * x_1 + c

you want to minimize the prediction error.

\[\text{prediction error: } = \sqrt{ \sum_{i=1}^{n} (y_i - (a + b x_i))^2 }\]Heron’s method

Let’s travel back to 50 AD in ancient greece and meet Ἥρων ὁ Ἀλεξανδρεύς aka Heron of Alexandria

He invented the first steam engine (Aeolipile) and first vending machine!

And also something called Heron’s method to calculate the square root of a number. Also called for unknown reasons Babylonian method.

Simple algorithm to calculate the square root of 2.

Start from x_0 for instance x_0 = 1

Then repeat

- x_{n+1} = 1/2 (x_n + 2 / x_n)

until x_{n+1}^2 is close enough to 2.

in python:

x = -1

precision = 0.0001

for i in range(100):

x = 0.5 * (x + 2 / x)

error = abs(2 - x**2)

print(i, 'x : ', round(x,8), 'error : ', round(error, 8))

if error < precision:

break

print('\nx : ', round(x,10), 'x^2 : ', round(x**2,10))

Extremely efficient!

It has all the ingredient of the Method of least squares.

- the prediction : (x_n)^2

- the error : abs(2 - x_n^2)

- the learning rate : 0.5 that dictates by how much we wan to modify the estimated value.

Back to Machine Learning

The context: you have a dataset with features (columns) and a target variable.

for instance, the titanic dataset, the iris dataset, the house prices dataset, etc.

On this page of the most popular datasets

Notice how we can filter by

- data types

- tasks

- feature types

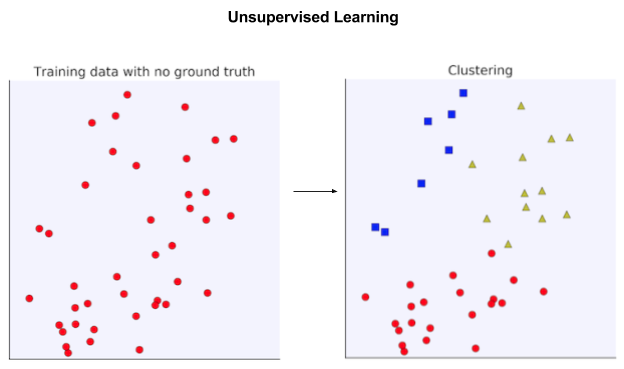

Regression vs Classification vs Clustering

On one side we have supervised learning (classification and regression) and on the other side unsupervised learning (clustering).

- Unsupervised: no target, you use all columns to find patterns

- group samples by similarity (user segmentation, topics in corpus, etc)

- Supervised: on column is the target you want to predict

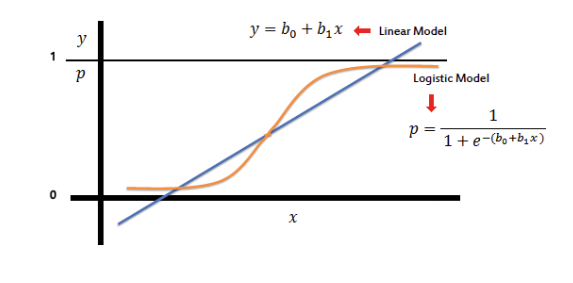

Linear regression vs Logistic regression

the output of a linear regression is a real number (as in decimal number) without any limit

if we forced this number into a range of [0,1], then we could interpret it as a probability.

- 10% = 0.1

- 99% = 0.99

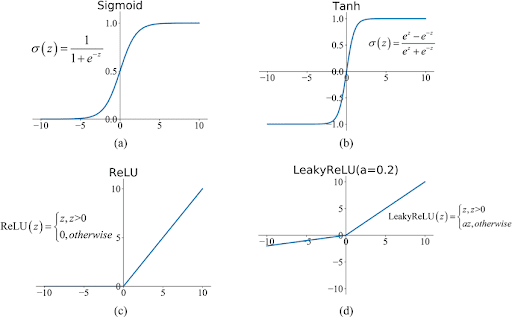

Introducing the logit / sigmoid function

- takes any number and transforms it into a number between 0 and 1

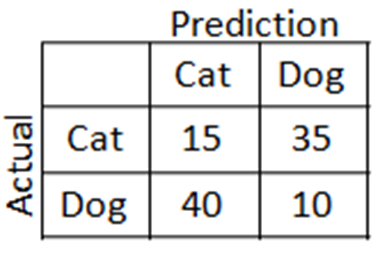

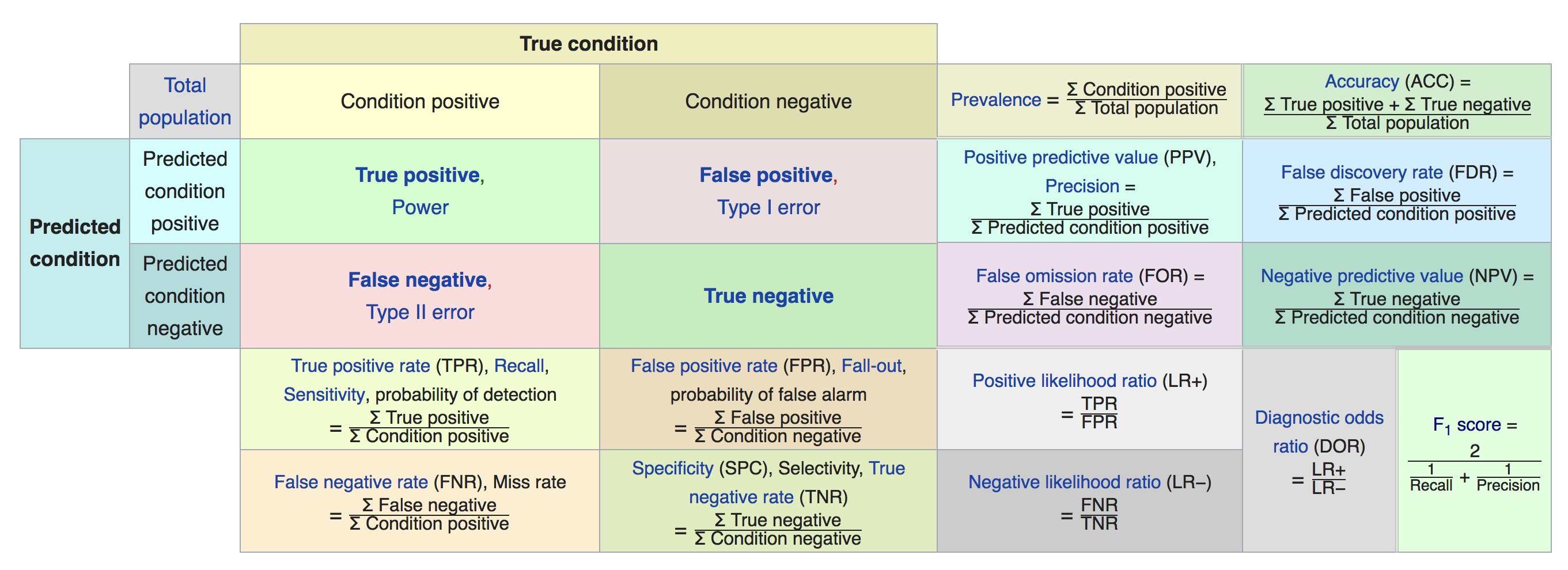

Evaluation Metrics

- regression: mean squared error (see Heron’s algo), MAE, RMSE, R^2

- classification: accuracy, precision, recall, f1 score etc etc etc

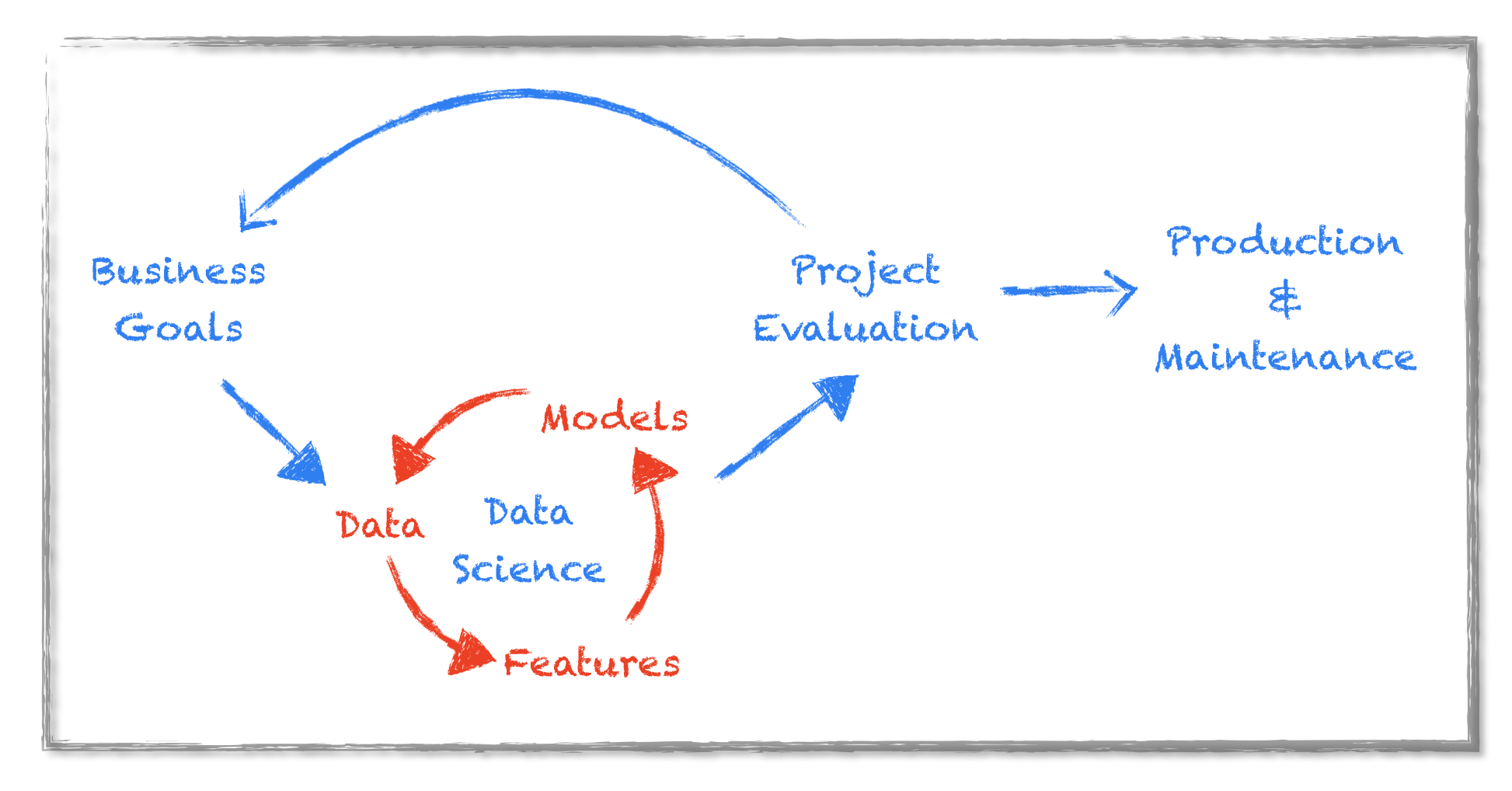

Iterative Work process

- get the data

- clean the data

- select features based on domain knowldged

- select features automatically

- split the data into train and test

- select a model

- train the model

- evaluate the model

- back to square 1

Most important families of models

- linear models : linear regression, logistic regression, SGD, …

- tree based : ensembling, boosting

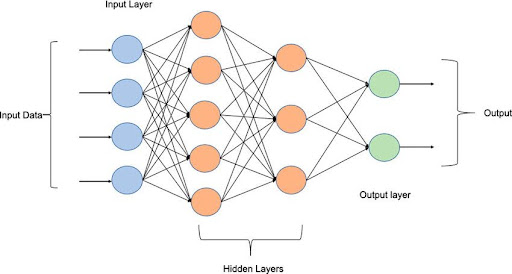

- neural networks

- perceptron : 1957, simple algorithm. MLP. can handle non linear

- backpropagation : 1986 (Yan LeCun),

- Winter of AI

- breakthrough : image classification competition. datasets are available

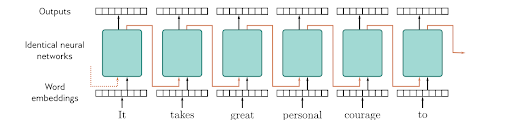

- LLMs

- embeddings : 2013 word2vec

- transfomers architecture: 2017 : context embedding

Auto ML

- Google AutoML, AWS Sagemaker etc

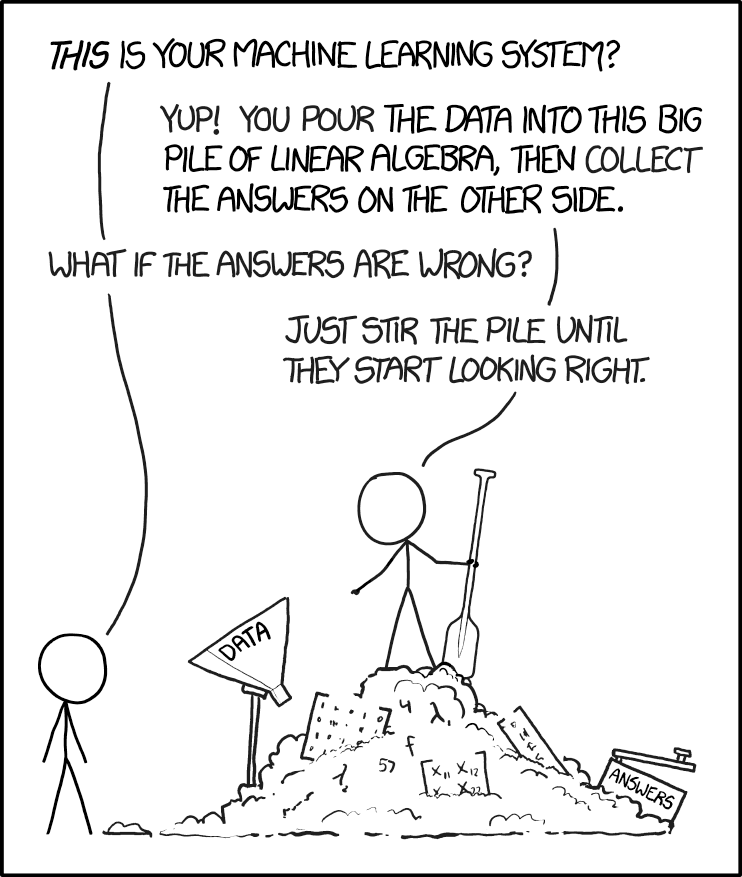

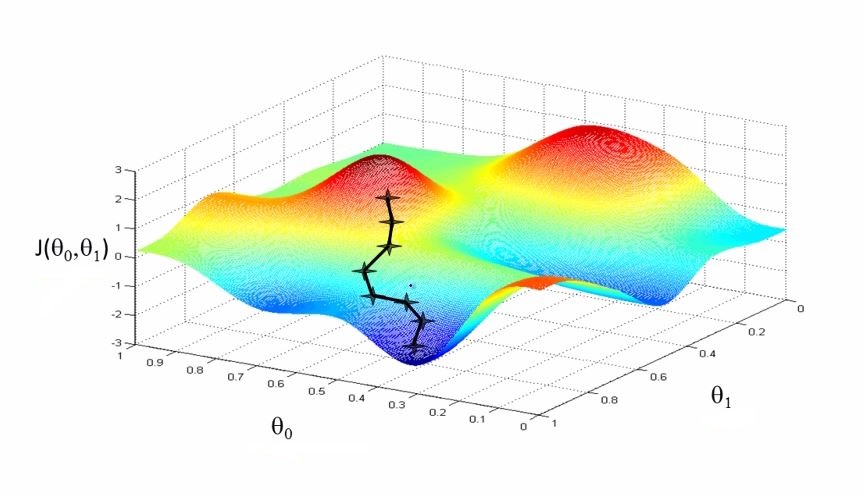

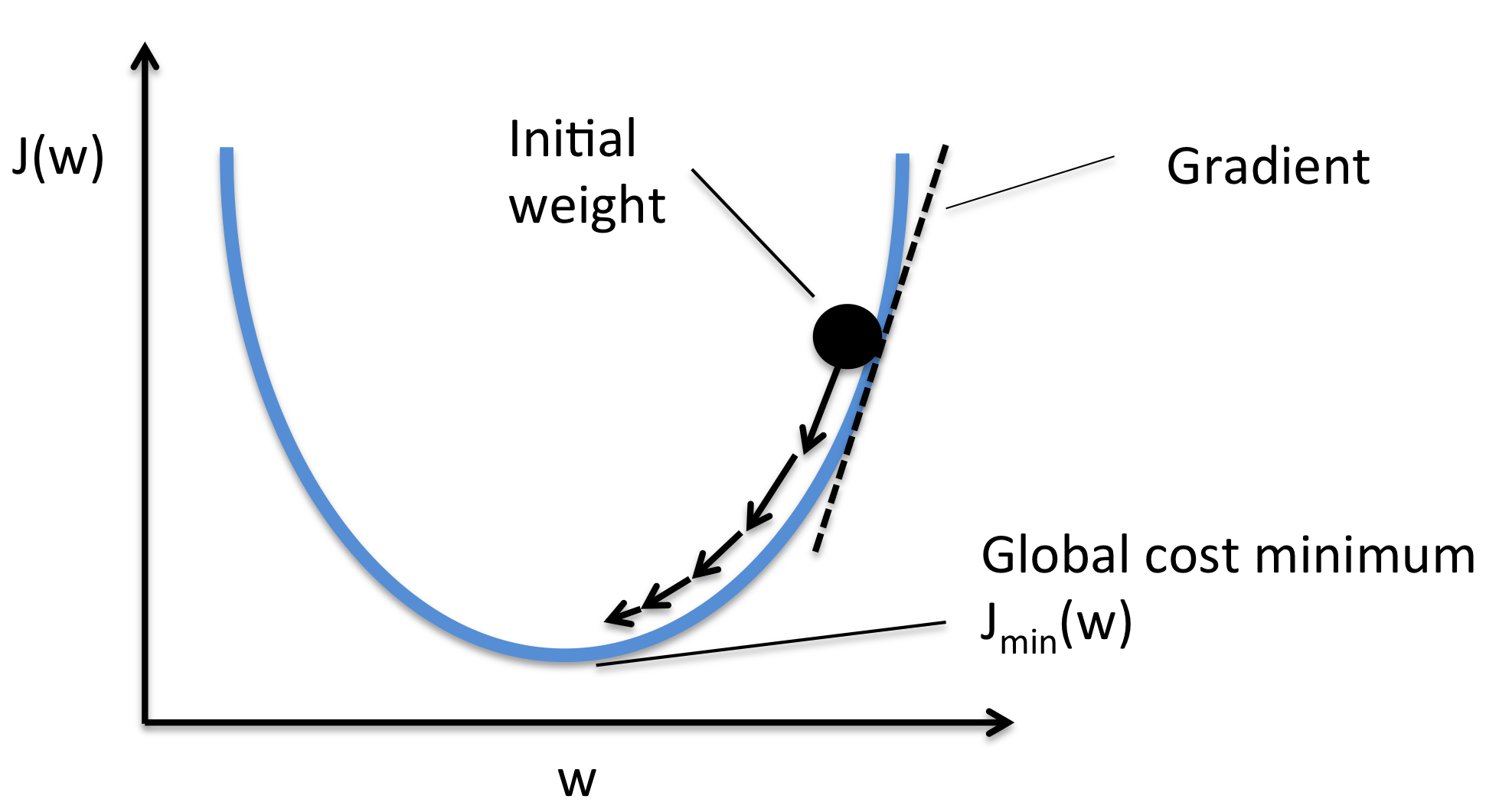

Gradient descent

- context: linear model : set of coefficients. think linear regression with many coefficients

start with a set of arbitrary coefficients (all zeroes or ones for instance)

- calculate the error and its derivative (the slope)

- update the coefficients a little (tune with a parameter called the learning rate)

- until the error is very small

In a way very similar to Heron’s method.

The goal of gradient descent is to find the local minima of a function.

and

- From Gradient descent

Wikipedia:

Gradient descent is generally attributed to Augustin-Louis Cauchy, who first suggested it in 1847.Jacques Hadamard independently proposed a similar method in 1907. Its convergence properties for non-linear optimization problems were first studied by Haskell Curry in 1944

Each iteration uses all the data.

The basic idea behind stochastic approximation can be traced back to the Robbins–Monro algorithm of the 1950s

Each iteration uses a tiny subset of the data (batch mode) or even just one sample.

All current genAI models are trained with some variant of the SGD!

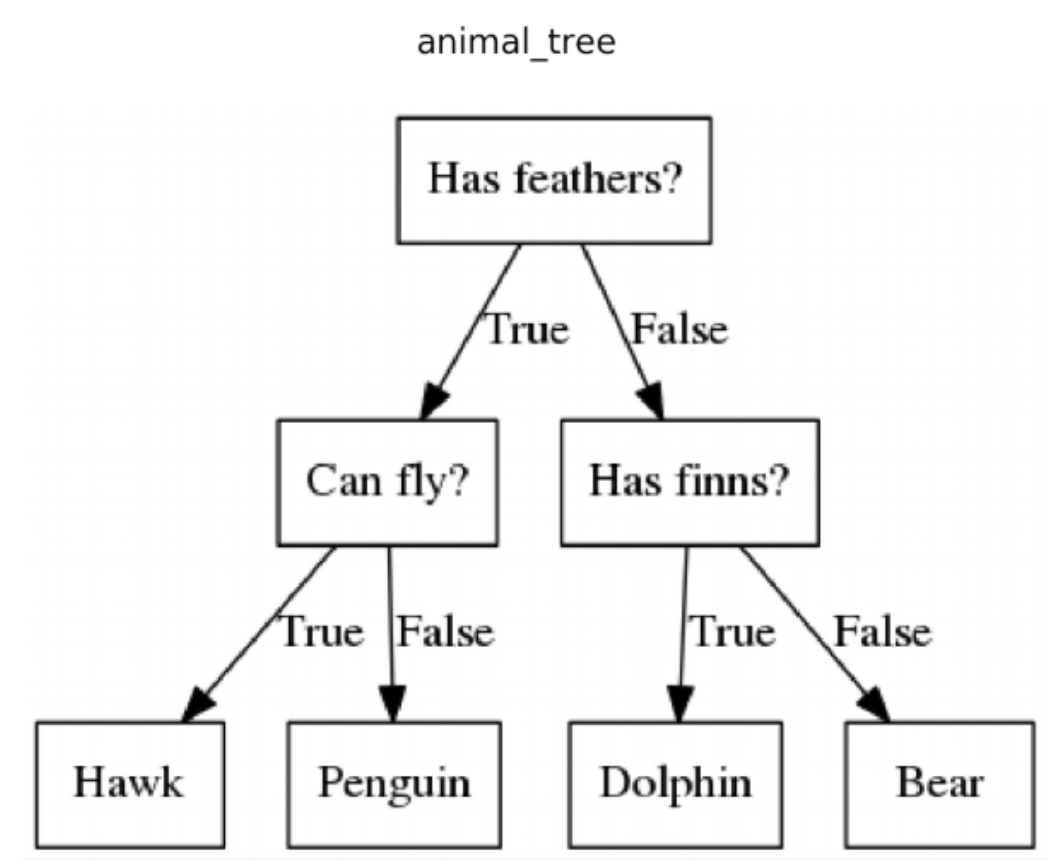

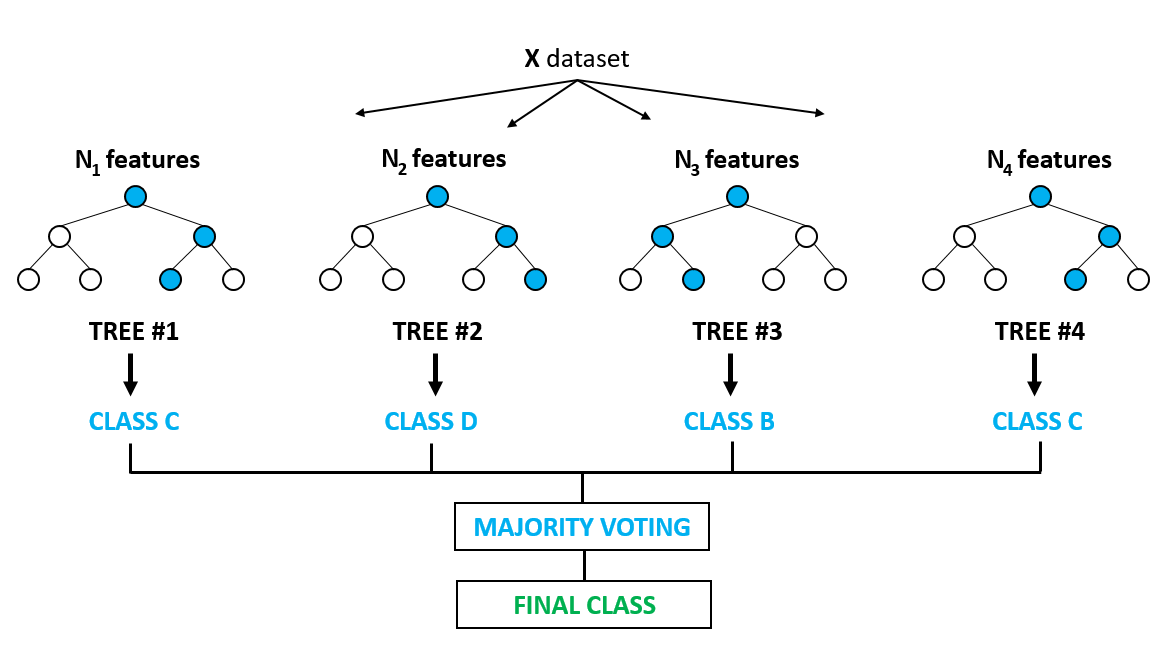

Tree based models

- decision trees

- random forests

- gradient boosting (ensembling + SGD)

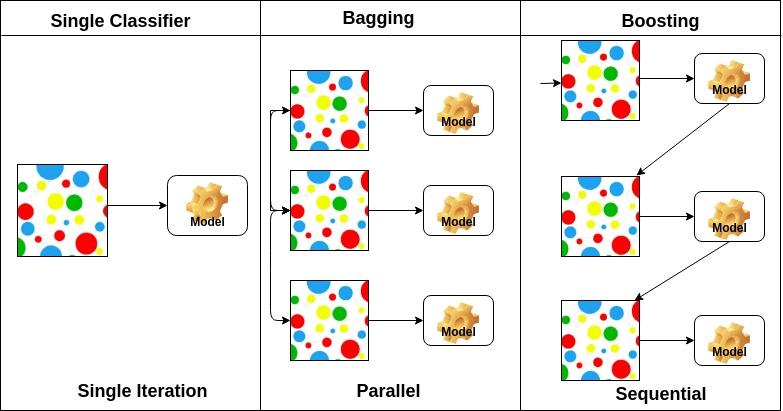

Ensembling / Bagging vs Boosting

- train many weak learners or laerners that tend to overfit

- combine them to get a better model

- averaging the output : bagging

- sequentially narrowing on the errors : boosting

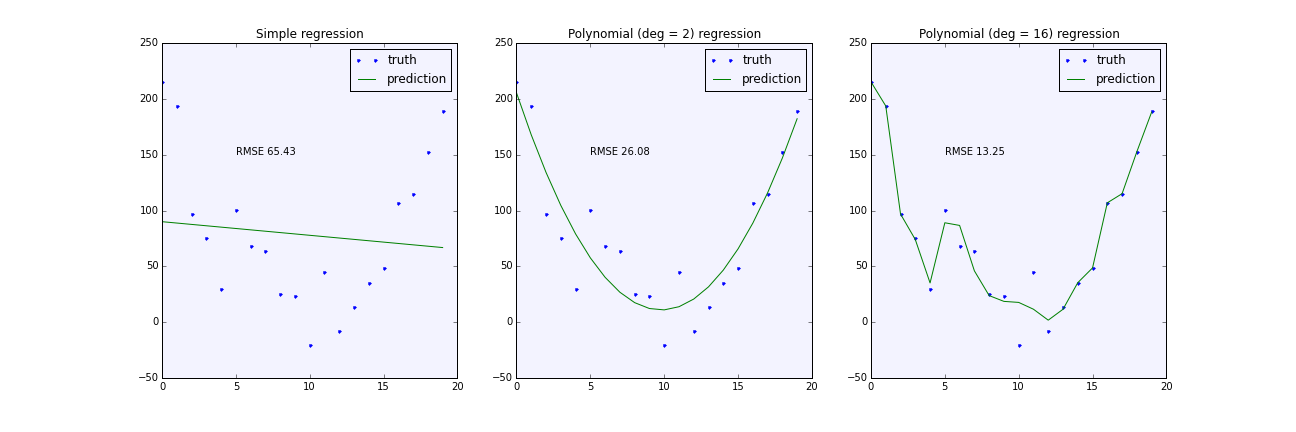

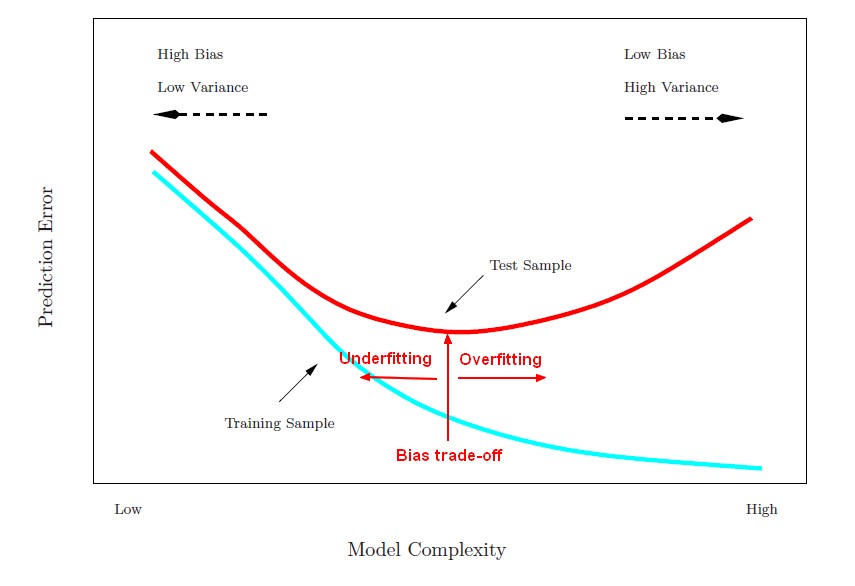

Overfitting and regularization

Splitting the data

You only have a set of data. You want to

- train the model => it learns the patterns in the data

- evaluate the performance of the mode with some choosen metric

But you only have a set of data.

So you split the dataset into train and test subsets

cross validation: In fact you do that multiple times with different splits and tune the model so that it performs well on average over all the splits.

This way the training data is not very different than the evaluation data. think outliers, missing values, under representation of a class etc

In the end you want your model to perform well on new unseen data.

Overfitting

Overfitting is the enemy of the data scientist.

More complex models, are better at learning the training data.

The model is so good at learning training data that it will perform great on the training data but poorly on the test data. And therefore on the real world data that it has nott seen yet.

Can’t generalize.

Detect overfit by comparing the error on the training data and the error on the test data.

if it is too high on the training data and too low on the test data, it is overfitting.

Regularization

Techniques to avoid overfitting.

- adding data

Adding constraints on the model

- trees

- pruning trees: limiting depth

- minimum split, or samples per leafs

- Gradient based models

- L1/L2 regularization

- early stopping

Randomly drop some features at each iteration.

- dropout

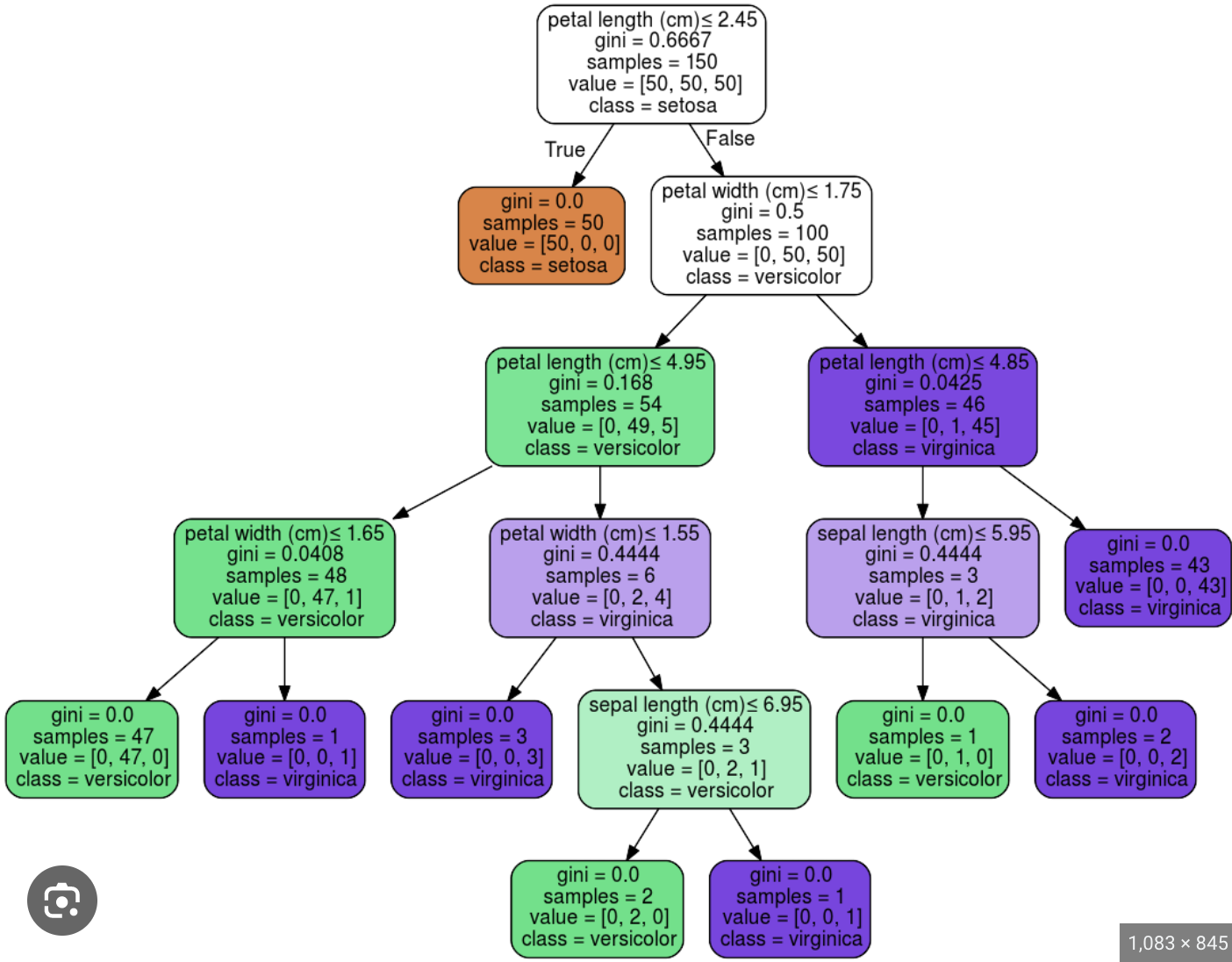

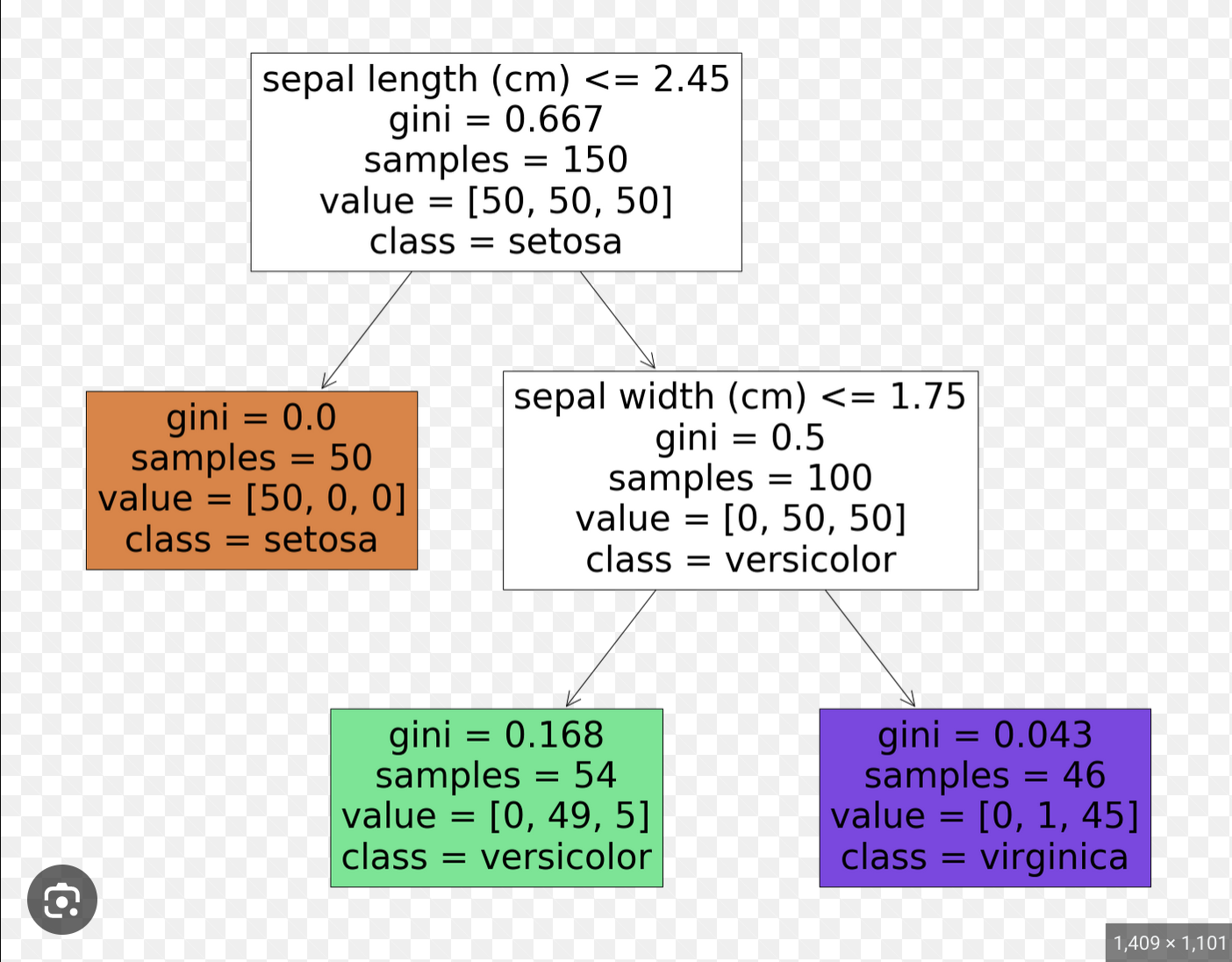

Tree pruning

This is a decision tree trained on the Iris dataset. It is overfitting.

The same tree but limited to a depth of 2

No longer overfits, but poorer performance.

So train many trees (pruned or not pruned), each on a random subset of the data. then average

You have random forests.

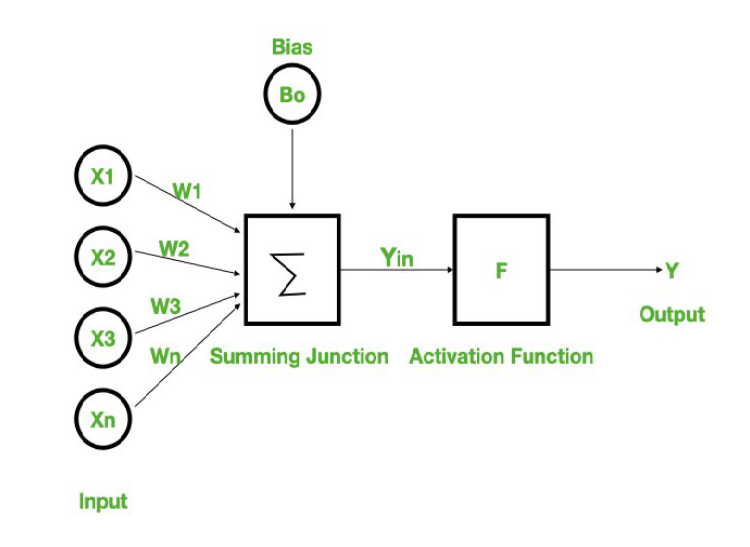

Activation function is what makes the model non linear.

Algorithm Perceptron

Initialize weights (including a bias weight) to 0 or small random values Set a learning rate (a small number, e.g., 0.01)

For each training example:

Calculate the weighted sum:

sum = (input1 * weight1) + (input2 * weight2) + ... + bias_weight

Apply a step function to decide:

If sum >= 0, output = 1

Else, output = 0

If the output is wrong:

For each weight:

weight = weight + (learning_rate * (true_output - predicted_output) * input)

bias_weight = bias_weight + (learning_rate * (true_output - predicted_output))

Repeat for multiple passes over the training data until errors are minimized

and in python

import numpy as np

# Training data: each row is [input1, input2, true_output]

training_data = np.array([

[0, 0, 0],

[0, 1, 0],

[1, 0, 0],

[1, 1, 1],

])

# Initialize weights and bias

weights = np.array([0.0, 0.0])

bias = 0.0

learning_rate = 0.1

# Training loop

for _ in range(10):

for data in training_data:

inputs, true_output = data[:2], data[2]

# Calculate weighted sum

weighted_sum = np.dot(inputs, weights) + bias

# Step function (1 if >= 0, else 0)

predicted_output = 1 if weighted_sum >= 0 else 0

# Update weights and bias

error = true_output - predicted_output

weights += learning_rate * error * inputs

bias += learning_rate * error

# Test the perceptron

for data in training_data:

inputs, _ = data[:2], data[2]

weighted_sum = np.dot(inputs, weights) + bias

print(f"Input: {inputs} -> Output: {1 if weighted_sum >= 0 else 0}")

Multi layer perceptron

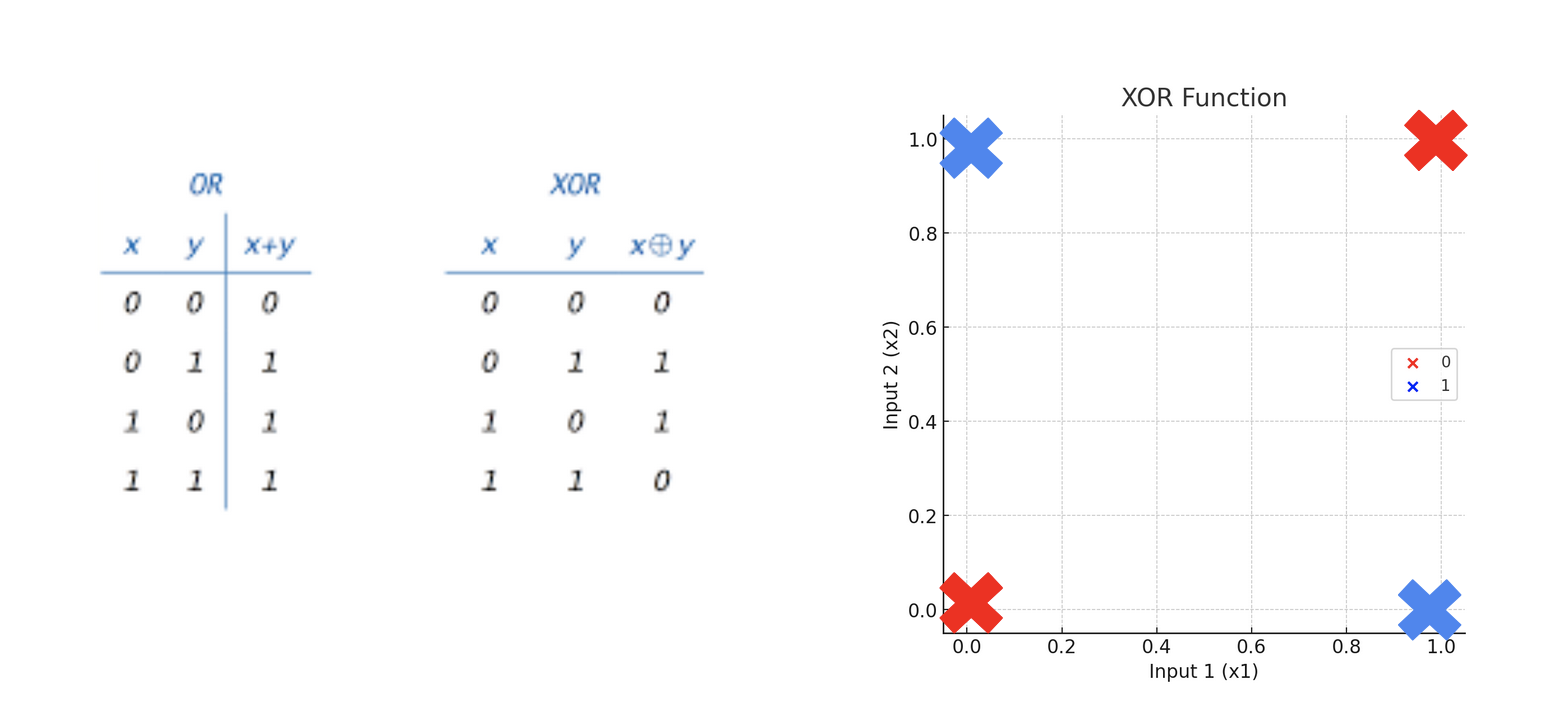

Single-layer perceptrons are only capable of learning linearly separable patterns

Can learn AND but not XOR

a feedforward neural network with two or more layers (also called a multilayer perceptron) had greater processing power than perceptrons with one layer (also called a single-layer perceptron). (wikipedia)

see Notebook: XOR vs AND

Backpropagation

1980s: Development of backpropagation

Regularisation for Neural Networks

On top of L2/L1 regularisation, dropout consists in randomly setting some weights to zero during training.

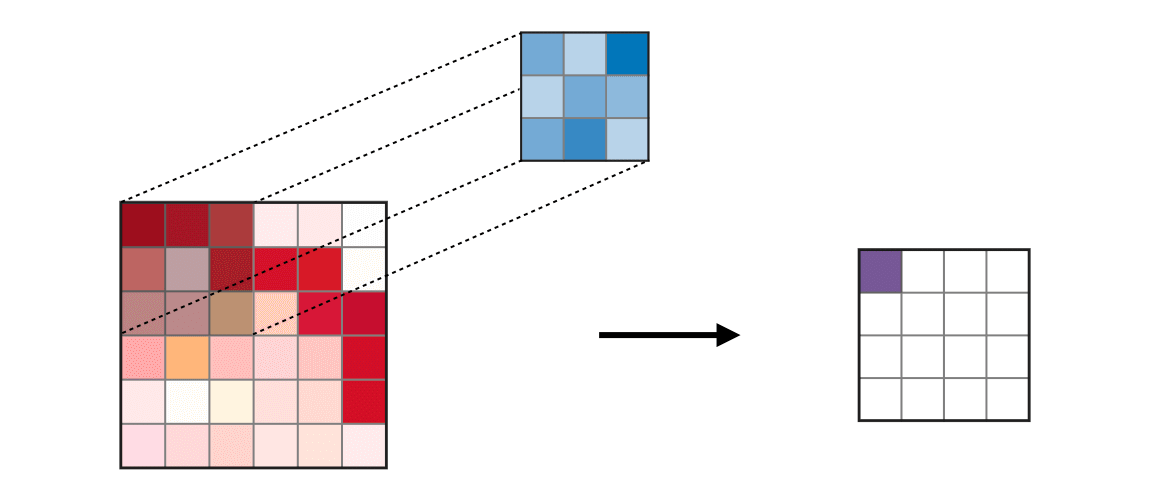

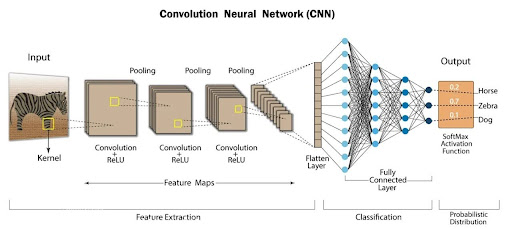

CNN : convolutional neural networks

Replace the linear regression with convolutions.

Excellent for

- images

- time series (1D)

Each convolution layer extracts features from the previous layer. It zooms out and abstracts the patterns

Typical CNN

RNNs : Recurrent Neural Networks

Great for time series, NLP and any type of sequential data

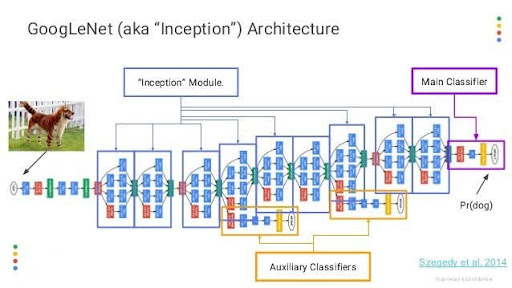

Example of a more complex NN : Inception

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inception_(deep_learning_architecture)

Inception[1] is a family of convolutional neural network (CNN) for computer vision, introduced by researchers at Google in 2014 as GoogLeNet

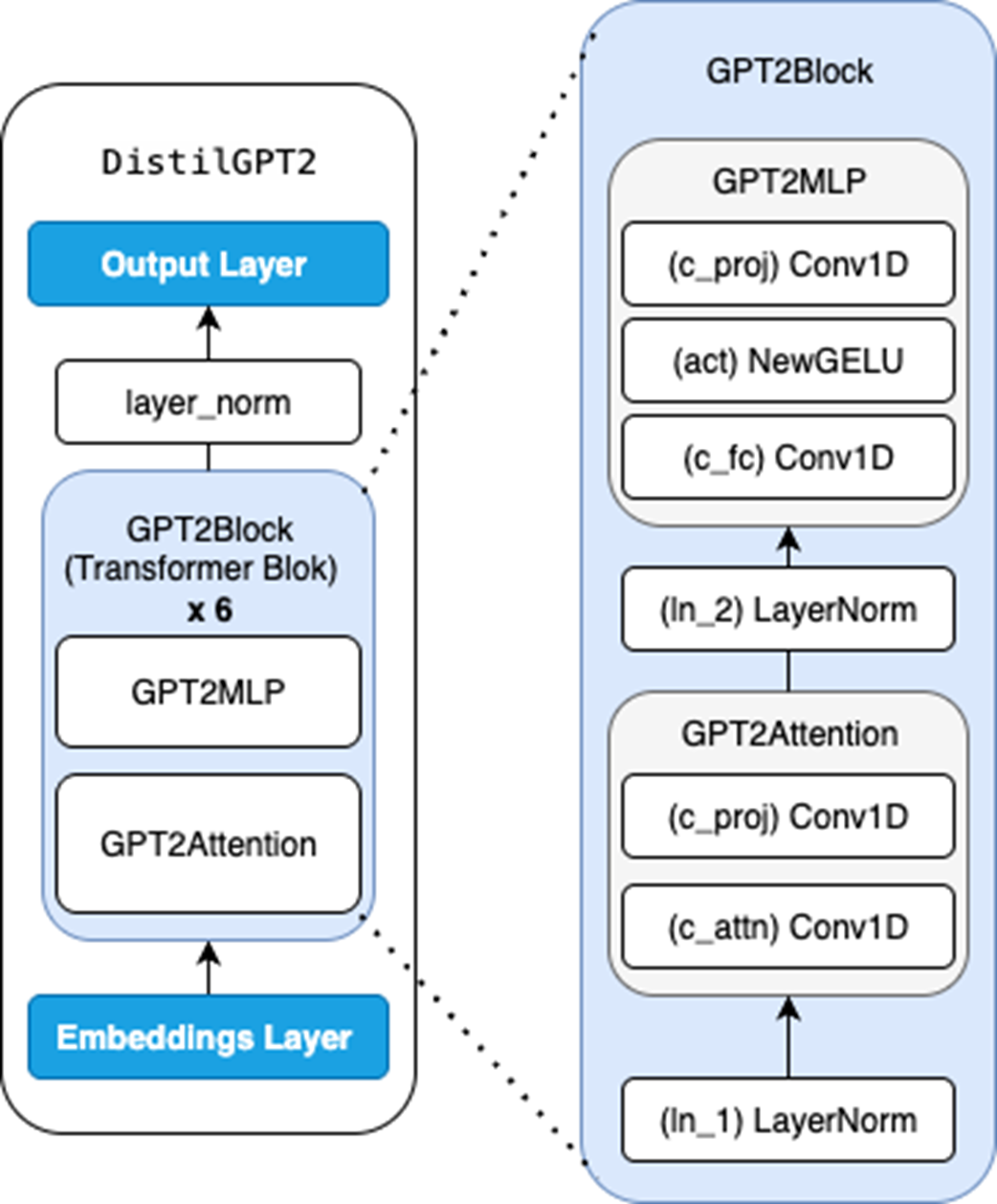

Transformers

Architecture of GPT-2

see

see